Today marks World Oceans Day, so we direct you to Blogfish, which has a "carnival of the blue" going on with a compendium of thoughtful posts from blogs everywhere on the subject.

Today marks World Oceans Day, so we direct you to Blogfish, which has a "carnival of the blue" going on with a compendium of thoughtful posts from blogs everywhere on the subject.

The suspension of a mega-organic dairy in California continues to generate attention, with the most recent from a neighbor who had the foresight to take video of the operation and post it on her blog, Rebuild from Depression. She also has a very insightful post about the operation that I recommend others to read.

What this work shows is that producers and consumers are very interested in transparency and, with the use of the Internet, will out those producers who are skirting the regulations. This is what transparency is all about and what underpins organic and sustainable foods.

Without further adieu, on to the video eulogy. (Note on video: It views better if you download the whole thing before playing unless you have a fast connection).

By Samuel Fromartz

A supermarket is a supermarket except when it's not, the Federal Trade Commission said this week.

The commission threw down the gauntlet and opposed the combination of Whole Foods and Wild Oats, because their merger would create a monopoly in that protected enclave, the natural foods business. This would lead to higher natural and organic food prices and store quality would go down. Whole Foods already gets slammed for its prices. Now they would move higher? And the stores are going to look like crap? This is a recipe for business success?

I find this view, at the very least, myopic and want to send the staff copies of my book. (Anybody willing to put up the chump change for this action?) Considering that every other supermarket chain has launched a surprising array of organic food products and that leading products, such as organic bagged lettuce, are sold in three out of every four grocery stores in the nation, the idea of a separate natural foods business is something of a fantasy. According to the Times:

Neil Currie, an analyst at UBS Investment Research, said in a note to investors that the F.T.C.’s actions were “somewhat at odds” with the recent blurring of lines between stores like Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s and more conventional chains like Publix and Wegmans. He said that 74 percent of natural and organic foods were now sold through mass-market channels like conventional supermarkets.

Yesterday, Natural Food Merchandiser came out with its survey which pegged the retail natural foods business at $46 billion. The share held by conventional grocery stores: 50 percent, or $23 billion. Whole Foods does not have the remaining 50 percent. In fact, its sales last year were $6 billion. Wild Oats annual sales were a little over $1 billion, which gives them a combined 15 percent of natural food sales.

Whole Foods also decided to pursue this merger with a very old nemesis once it became clear that competition was arising from new entrants, such as traditional grocery stores. Even Wal-Mart, the biggest supermarket in the nation, whose sales are bigger than the next-six biggest chains, is selling organic food. In other words, this merger was a defensive strategy by Whole Foods to protect against new competitors, not to get a lock on the market. That's impossible, now that natural and organic foods have gone mainstream.

Maybe if Whole Foods sold Coca-Cola, or other products with a lot of high-fructose corn syrup and artificial flavors and colors, the merger would go through. After all, then it would be just be another supermarket. But it doesn't, so it's not.

Advice to Whole Foods CEO John Mackey: Call Bill Gates and get the number for his lawyer. Microsoft's a true monopoly and through many legal actions they are still doing just fine.

Carol Ness in the SF Chronicle has a good follow-up to our breaking story yesterday about the Vander Eyk dairy being stripped of organic certification in California. This is a very significant enforcement action in the organic world, though it begs a few questions.

If confinement dairy practices aren't corrected, then the next phase will be to design an additional label for organic milk that truly reflects organic practices such as pasturing - a prospect that is now being floated. That would be a shame and a cause of additional consumer confusion but that will happen if the USDA's National Organic Program does not move forward with a pasture rule that would outlaw these kind of operations.

Dole Organic began putting a little sticker on its bananas earlier this year, allowing consumers to see where the fruit was grown. I blogged on this months ago. Now they've taken the program further, allowing for interaction with the farm. Dole has posted an email one customer wrote and then an amazing number of responses from workers on the banana plantation in La Guajira, Colombia.

Photos: Dole Organic

Among a few choice quotes:

"I evaluate the agronomical practices at the banana fields. Your letter made me feel that my work is appreciated. Thank you very much!" - Dulcinis Atencio

"You said you will keep us in your mind every time you eat an organic banana, we promise to keep you in mind every time we pack your bananas. Thank you for your letter." - Midelfi Mejías

"Everything started with this small sticker with the three digits... It is hard to believe that this tiny piece of paper created a beautiful link between you and all of us in Don Pedro ...I put the stickers on the organic bananas." - Tatiana Barros

OK, I know this is PR. I know the statements come through the company. I know this reveals little about the actual operation. But the appreciation expressed by the workers was pretty amazing, as if they were finally recognized for growing food! What a thought.

I encourage people to read this new experiment in the farmer-consumer connection over thousands of miles. Thanks to Luis Monge, regional certification officer for Dole's Organic Program, for the shout out on this development.

By Samuel Fromartz

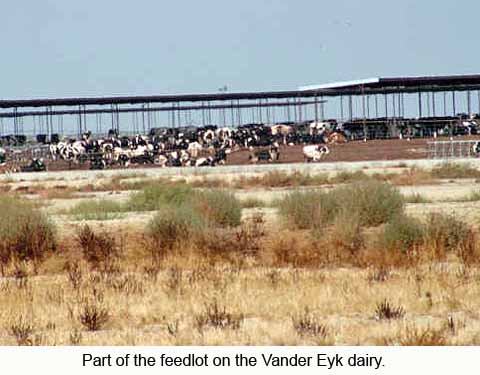

In a sign that pressure is mounting on big confinement organic dairy farms, Quality Assurance International, a major organic certification agency, has yanked certification for the Case Vander Eyk organic dairy in California, an operation with an estimated 3,500 cows.

This dairy in the central valley of California has been the subject of complaints by the advocacy group, Cornucopia Institute. But QAI's decision marks the first time a certifier has suspended a big confinement dairy, though these farms have been criticized for years.

Photo: Cornucopia Institute

"The process took quite a long time," one source with direct knowledge of the situation said, because of the review requirements under the USDA's National Organic Program.

Once certification is suspended, as it was in this case in mid-May, the operation can no longer sell its products as organic. It can, however, appeal the certifier's decision to the NOP, which then reviews the details of the case.

One source said the farm didn't comply with organic regulations in a number of areas, including pasture.

The Vander Eyk dairy was among several large-scale farms that became lightening rods in the organic industry over the past several years as the organic dairy market expanded at 20-30 percent a year.

Several large scale farms came on line and others were looking to transition to the market. But many organic dairy farmers, consumer groups and advocates strongly objected to these confinement dairy farms that offered little or no pasture to their milking cows.

Complaints were filed with the USDA's National Organic Program and efforts redoubled to tighten up the regulatory language requiring pasture so these large-scale confinement farms would be shut down.

The Vander Eyk dairy, which had both conventional and organic operations, had been selling milk to Horizon Organic, but it was yanked as a supplier when its contract ran out in 2006, because it no longer met the company's standards. Horizon, the largest organic milk company, had come under a lot of pressure for a large-scale dairy farm it owns in Idaho. But it has since invested millions in the farm to add pasture in a process that is now nearly complete.

Horizon Organic has backed a tighter organic pasture standard, calling for cows to graze at least 120 days on pasture with at least 30 percent of the cow's nutritional needs coming from fresh grass. Organic dairy farmers nationwide are pushing for this strict language and it is currently under review by the NOP.

The Vander Eyk farm was among several, such as Aurora Organic in Colorado, which did not offer meaningful pasture access to its cows. But the language was so vague in the current regulations that it became a loophole that allowed organic confinement farms to exist, much to the dismay of many organic proponents.

"Your headline should read 'Case Closed,'" said Mark Kastel of Cornucopia Institute.

But the final chapter of these big organic dairy farms has yet to be written.

Natural Selection Foods, the company at the heart of the spinach e. coli outbreak last fall, is now testing product intensely. And it continues to find dangerous microbes regularly. Check out my report on NPR.

What a mouthful, but it came to mind after reading this thoughtful post in Blogfish, a blog on the oceans by Mark Powell, US director of Fish Conservation-Ocean Conservancy:

Conservationists should try to help create a viable path to sustainability. It’s not good enough to articulate some grand high goal, and stand back and criticize anyone who doesn’t meet it. That’s preachy, soapbox environmentalism, and it’s not going to solve the problem. It’s fine to talk about ultimate goals, but it’s even better to help fisheries get to the goals. I think too many of my colleagues don’t see the need to create a path to sustainability, they prefer to talk about how high to "set the bar" of sustainability. And many think the most noble thing is to set the bar so high that there isn't one fishery in the world that meets the standard. Those can be fine ideas, but they don't have much practical value.

Eastern cod has been a classic story of overfishing, with fish populations crashing and the fisherman along with it. That's why I found it curious that hook-caught Georges Bank cod off the eastern seaboard is going for certification by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) as a sustainable fishery.

Eric Brazer Jr., of the Cape Cod Commercial Hook Fishermen's Association, told The Cape Codder that last fall the hook and line fishing sector off Cape Cod, Mass., passed the "first assessment to getting certified" under rigorous sustainable harvesting standards set by the MSC.

MSC, founded by World Wildlife Fund and Unilever, hasnow certified 21 other fisheries around the world as "sustainable."

The news on cod was reported by Sustainable Food News (requires subscription) in March and I have seen no follow-up anywhere else. Perhaps prospects for the fish have changed, if you consider this small item in a Green Guide story from 2003:

According to NMFS (National Marine Fisheries Service), the cod population of New England’s Georges Bank has yet to recover, despite restrictions placed on its fishing since 1994. This year, Canada shut down all its cod fisheries to protect the species’ plummeting numbers. “We’ve seen species after species, such as the Georges Bank cod and Bocaccio rockfish on the Pacific Coast, that have collapsed under federal management,” says Susan Boa, program manager of the Seafood Choices Alliance (SCA). Lee Crockett, executive director of the Marine Fish Conservation Network, says that fisheries managers have allowed catches that were too large for too long, bringing about the collapse of these populations over the last decade or two.

Right now, Seafood Watch only recommends buying Pacific line-caught cod, because those fisheries have been managed sustainably. (Icelandic cod, not on this list, is also well-managed). But so far, the program advises to "avoid" Atlantic cod. Here's the current cod recommendations (click graphic to enlarge), but this may well change if Atlantic line-caught cod wins MSC certification. - Samuel Fromartz

Lisa Hamilton, a writer I hope more people will soon be familiar with, has an interesting take on ethanol from the farmer's point of view. "If you actually are a farmer, ethanol and the high corn prices it brings is looking less and less like a blessing -- and more like a curse," she writes on AlterNet.

While the price of corn may be at a glorious four dollars a bushel now, when it evaporates farmers will likely be left to pay for costs that reflect a boom but profits that reflect a bust. Considering that much of the biofuels industry is already calling corn an archaic fuel source, looking forward instead to cellulosic ethanol, this crash is bound to happen within the next few years. ... It's beginning to feel ominously like the lead-up to the farm crisis of the 1980s, when high times led to unsustainable debt. They fear that the near future holds widespread foreclosure, not rural salvation.

What Hamilton proposes is not a boom-and-bust cycle, but a way to ensure farmers get a fair price for their goods. "What farmers need in order to rebuild their communities and secure their farm incomes is not an ethanol boom -- or any kind of boom for that matter. They need a system that offers a fair return for their product all the time, not just during a fuel crisis."

Local and organic foods usually get slammed for being more expensive, the luxuries of rich people, elitist, and so on. I demolished the assumptions about organic consumers in my book, citing a body of consumer market research that has shown income has no bearing on an organic purchase. In short, people earning $150,000 a year are just as likely as those earning $50,000 a year to buy organic food. The Hartman Group, which studies such things, has found income one of the least useful indicators in targeting this market.

Now to the farmers' market, which also feeds such perceptions. Ethicurean points to Becks and Posh, written by Sam Breach, who actually took the time to compare farmers' market prices with Safeway supermarket. This was just not any farmers' market, but the San Francisco Ferry Plaza market, which has a reputation for being the most elitist in the nation. What did she find? On a fixed list of items, she spent 29 percent less at the farmers' market.

As for the elitist argument, we have thriving farmers' markets in wealthy and lower-income sections of Washington, DC. Actually, the latter, in Anacostia, operated by the Capital Area Food Bank and opening for the season next week, does well because it has no competition.  The neighborhood has had no supermarket since 1998 so the only food sources have been high-priced convenience stores and a lot of fast food joints that don't tend to offer fresh produce. In other words, fresh food could not be had at any price before this farmers' market opened.

The neighborhood has had no supermarket since 1998 so the only food sources have been high-priced convenience stores and a lot of fast food joints that don't tend to offer fresh produce. In other words, fresh food could not be had at any price before this farmers' market opened.

On this score, Whole Foods has been complaining for some time that people perceive it as pricey, when it's actually quite competitive compared with Trader Joe's and other supermarkets across the same items. In Washington DC, I've found they are the price leader on organic milk but have not done an in-depth comparison on other products. We encourage any shopper out there to do the comparison (so we don't have to).

- Samuel Fromartz

Columbia Journalism Review has an interesting take on the new food journalism, peeling back the curtain on the assumptions of sustainable ag advocates with a few swipes at Michael Pollan thrown in for good measure.