After years of complaints and aggressive public advocacy, the U.S. Department of Agriculture last week did what it should have done long ago: It forced the largest private- label organic milk company in the nation - Boulder-based Aurora Organic Dairy - to amend its farming practices so they comply with regulations.

The department also threatened to revoke the company's organic certification, which allows it to sell organic milk, if it failed to comply during a one-year probationary period.

This enforcement action was among the most significant the USDA has taken to protect the organic marketplace. Earlier this year, it shut down a big organic dairy in California, which also flouted the regulations.

It's a win for organic consumers, ensuring that the private-label organic milk they are buying for $5 to $6 a gallon in the supermarket actually is organic.

It's also a win for the majority of organic dairy farmers, many of whom run much smaller farms and face higher costs as a result of complying with the letter of the law.

Right now, the organic industry has in place a comprehensive certification program to make sure farms and food producers do things right. You can actually see the certifier identified on the organic food product you're buying.

Consumer trust at the heart of the market depends upon every producer and certifier following these regulations.

But this system works only if the certifiers know what they are doing and the USDA takes action to bring scofflaws into line. Until two weeks ago, the system broke down on both counts.

In its "Notice of Proposed Revocation," the USDA alleged that Aurora was in "willful violation" of the organic rules in 14 instances, primarily at its farm in Platteville.

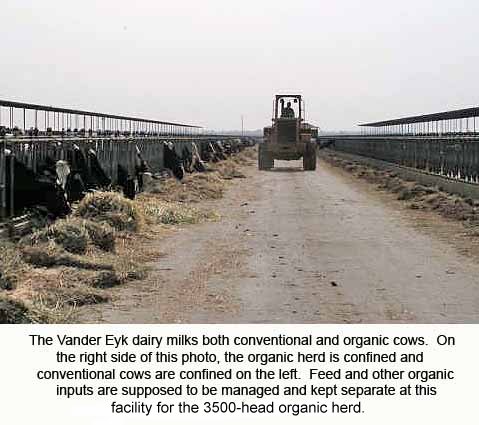

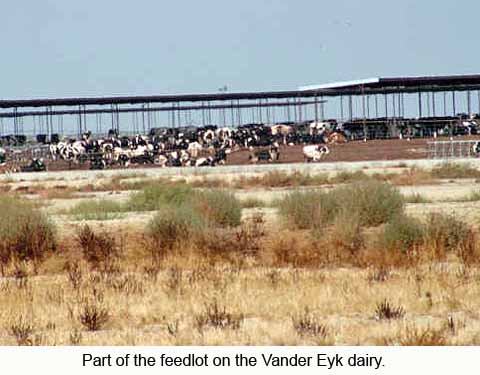

Among the most egregious, Aurora Organic Dairy did not adequately graze its animals on pasture. It also brought cows onto its farms that did not meet the requirements of organically reared livestock.

Aurora countered that its farms always have been certified organic.

True. And therein lies the rub. The Colorado Department of Agriculture, which certified Aurora's farming operations, fell down on the job.

It has agreed to step up training of its staff.

But the state certifiers aren't the only ones deserving of a failing grade. The USDA had been getting loud complaints about Aurora Organic since 2005 from the farm advocacy group, Cornucopia Institute, and competing organic dairy farmers. Aurora was also open about its minimal grazing policy, saying this method, which squeezed thousands of cows into feedlots, was better suited to arid Colorado.

It took two years for the USDA to investigate the complaints and then negotiate a settlement with the company. (This stems from another problem: The USDA has a staff of about a half-dozen people to oversee the entire $17 billion organic food industry in this country.)

Aurora was not standing still at this time, aware that pressure was building. It opened another farm in Colorado designed to increase grazing access for its cows. It began cutting back the size of its massive herd in Platteville (more than 4,000 cows at one point) and plans to reduce the figure to 1,250 animals. It razed buildings to add pasture.

Given the experience of Aurora's founders, who have been in the organic dairy business since the early 1990s, it stretches credulity to believe they did not know what they were doing. What seems more likely is that they made a calculated bid to game the system while building a fast-growing, venture-backed organic dairy business, only correcting things once the action got too hot.

Under the pressure of the USDA consent agreement, Aurora will no doubt complete its program and get back in line.

Hopefully, the system will now work - with certifiers and regulators preventing this kind of case from ever happening again.